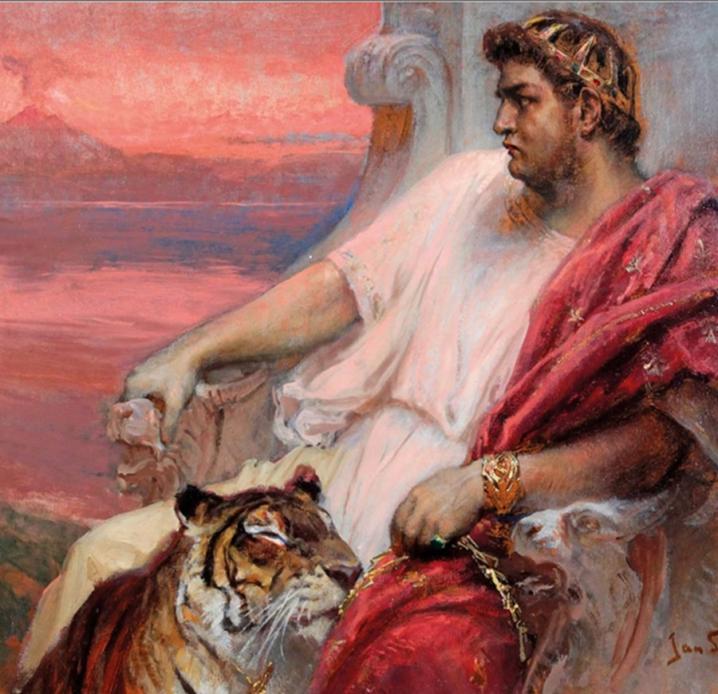

Was Nero really a monster?

A heartless tyrant and narcissist who ordered the murder of his own relatives to cling to power: This is the profile most usually associated with Nero, the fifth and last emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. It’s not surprising that this image prevails. Classical sources presented Nero as a depraved, oversexed tyrant with an erratic personality, who lived and ruled under the thumb of his ambitious mother, Agrippina the Younger. But curiously, while the ancient authors focused on his ruthless egotism, the political propaganda of Nero’s time also highlighted the emperor’s clemency. Despite the fact that Nero’s government, especially in its final years, systematically persecuted Christians and wiped out dissidents, the Roman Empire under Nero also experienced some of its greatest moments of economic and cultural dynamism.

An unworthy emperor?

When Emperor Claudius died suddenly in A.D. 54, Nero succeeded him to the throne at only 16 years old, leapfrogging over other members of the Julio-Claudian ruling dynasty. Claudius had adopted Nero after marrying Nero’s mother (and Claudius’s own niece), Agrippina the Younger. By naming Nero his heir, Claudius overlooked his biological son Britannicus, but Nero enjoyed popular favor and the support of the Praetorian Guard.

A marble bust of a woman with short curls and a missing nose

Nero’s mother, Agrippina the Younger, brought him to power, then tried to remove him from it—for which he ha…Read More

Album/Prisma

It was Agrippina, Claudius’s fourth wife, who had maneuvered her son into pole position. She had persuaded Claudius to adopt Nero in A.D. 50, and then to allow Nero to marry Claudius’s daughter Octavia in A.D. 53. According to accounts of ancient Roman writers, the following year, once Agrippina was confident Nero’s succession was assured, she had Claudius poisoned.

The ancient authors who depicted Agrippina as a murderess and framed Nero as a cruel tyrant may have had their own agendas. They resented the fact that Nero’s bureaucratization of the imperial administration took power out of the hands of the senatorial class to which those authors belonged. His suppression of indirect taxes in A.D. 58 resulted in greater participation of the common people in trade, which also displeased the aristocracy.

(Roman Empress Agrippina was a master strategist. She paid the price for it.)

Given these grievances, it is likely that ancient authors amplified narratives to discredit him. Among other misdeeds, the sources attribute dozens of homicides to Nero. While he, like many Roman emperors, undoubtedly caused deaths, many of the murders he is accused of seem improbable if the circumstances surrounding them are analyzed.

An engraving shows the side profile of a man with a beard and fabric draped over shoulders

Historians Suetonius and Tacitus (the latter shown in this 1830 engraving) both provide key information on Nero’s rule.

Mary Evans/Scala, Florence

For example, according to Tacitus, the Roman orator, politician, and historian writing around A.D. 100, Nero murdered his half brother Britannicus out of fear that Agrippina would form an alliance with him. Tacitus adds that Nero and his wife Octavia watched impassively as Britannicus died dramatically in the middle of dinner, while the other diners were in uproar. But when this ill-fated dinner happened in A.D. 55, Agrippina was at the height of her power and had no motive to support a pro-Britannicus change of government. Historian Anthony Barrett of the University of British Columbia argues that, in fact, Britannicus died as a result of an epileptic seizure.

Another gruesome episode attributed to Nero was the death of 400 people enslaved by the senator Lucius Pedanius Secundus. When one of them murdered Secundus, all 400 were sentenced to death. Some Romans rioted, demanding that the innocents be spared. Nero quelled the rebellion and ensured that the mass execution took place. But it was the Senate that had passed this law; Nero simply enforced it. And when some senators suggested that freedmen who had formerly been enslaved by Secundus be exiled from Rome as an additional measure of communal punishment, Nero refused. His position irritated the aristocracy, many of whom he had displaced from key positions in the imperial administration, replacing them with formerly enslaved freedmen in whom he placed his trust.

Life of the party

A lithograph shows 7 people participating in an ancient Roman bacchanal, with some playing instruments and one toasting wine

A colored lithograph from 1881 depicts Nero participating in a bacchanal.

Universal History Archive/Getty

According to Roman historian Suetonius, the young Nero was prone to acts of “wantonness, lust, extravagance, and cruelty.” With age, he wrote, the emperor’s vices only grew stronger:

He prolonged his revels from midday to midnight . . . Sometimes too he closed the inlets and banqueted in public in the great tank, in the Campus Martius, or in the Circus Maximus, waited on by harlots and dancing girls from all over the city.

Nero offered other examples of level-headed rule. Early in his reign, to avoid abuses of power by the sovereign and the Senate, he eliminated secret trials held intra cubiculum principis (literally “inside the prince’s chamber”), which involved the arbitrary condemnation or acquittal of a prisoner. Such private hearings had been common in the time of Claudius, and their suppression was recommended by Nero’s former tutor and mentor, the philosopher Seneca.

(Why some scholars are rethinking Nero.)

Popular with the plebs

A marble bust of Nero with a beard

This marble bust of Nero was carved around A.D. 60, when the ruler, in his early 20s, still enjoyed public support. No…Read More

the age of 20, Nero had already forged his own political style and instituted judicial and fiscal reforms benefiting the common people (plebeians). But his political vision was hampered by his mother Agrippina, who, after getting rid of all her rivals, threatened to remove her son from power. The first time that Agrippina was accused of plotting a coup d’état against her son, in A.D. 55, Nero showed clemency. Agrippina had allied herself with Nero’s rival Rubellius Plautus (the great-grandson of Emperor Tiberius). Nero forgave his mother and her accomplice, and he exiled others involved in the plot.

However, when Agrippina again took action against her son three years later, one of Nero’s advisers encouraged him to have her killed while making it look like an accident at sea. According to Tacitus, it was the freedman Anicetus who dreamed up the boat plot, but senator and historian Cassius Dio wrote that Seneca and Nero came up with the idea together. Either way, Nero gave orders to scupper the ship his mother was sailing on off the coast of Naples. Miraculously, Agrippina survived the shipwreck. Then, on March 23, A.D. 59, she was finally assassinated by Nero’s henchmen at her villa in Bauli.

It’s said that a well-known comic actor made a daring allusion in song to the murder. He sang: “Farewell to thee, father; farewell to thee, mother,” while doing a mime of eating and swimming. Claudius had been poisoned while eating dinner, and Agrippina had narrowly escaped being drowned.

The side profile of a woman on an old bronze coin

The likeness of Nero’s wife Octavia appears on a coin minted around A.D. 56–57. Nero banished Octavia to the rem…Read More

Despite these lurid events, which overshadowed Nero’s reign and detracted from his general policy of clemency, Nero retained considerable popularity by providing the people with bread and circuses. But the support of the common people began to wane when Poppaea Sabina, a beautiful Pompeian woman, appeared on the scene.

In A.D. 62, when Poppaea became pregnant several months into an adulterous relationship with Nero, the emperor decided to divorce his wife Octavia and marry Poppaea. To justify these actions, Nero accused Octavia of adultery with an enslaved person and exiled her to Campania, on the southwest coast. Outraged, the people began to destroy the public images of Poppaea in solidarity with the exiled empress. The revolt forced Nero to bring Octavia back to Rome, but he was now determined to sentence her to death. After facing a second false accusation of adultery, this time with Nero’s former accomplice Anicetus, the commander of the Misenum fleet, Octavia was sent to the island of Pandataria. There, some of the emperor’s assassins murdered her by slashing her veins and immersing her in boiling water.

A painting of a woman wearing nothing but a sheer shawl, with her name Sabina Poppaea, written below

A 16th-century painting of Poppaea Sabina, second wife of Nero.

The animosity the Roman people showed toward Poppaea wasn’t shared in other parts of the empire. In the Campania region, where Poppaea was born in the city of Pompeii, the imperial couple enjoyed popular support. On the walls of Pompeian houses (destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79) archaeologists uncovered graffiti reading “Hail Nero,” “Long Live Poppaea,” and “Hurray for the Emperor and Empress.”

(Pompeii still has many secrets to uncover—but should we keep digging?)

In fact, there was more Pompeian graffiti in favor of Nero than for any previous emperor, and the messages remained visible even after Nero had been sentenced to damnatio memoriae, the removal of all his public and private images and inscriptions after his death. Nero’s special popularity in Pompeii can be explained not only by Poppaea’s Pompeian origin but also by the favors that Nero granted the city. He contributed to Pompeii’s recovery after an earthquake devastated it in A.D. 62, and he visited in person to make offerings at the temple of Venus. Nero also gained popularity by allowing Pompeians to return to their amphitheater early.

Octavia’s gruesome murder

This painting shows Poppaea on a bed with Nero, gloating over the severed head of Octavia, presented to her on a platter.

One of the episodes that most damaged Nero’s reputation was the murder of his first wife, Claudia Octavia. According to the account by Tacitus in the second century, Poppaea Sabina, Nero’s lover, drove the murder of his wife Octavia, convincing Nero that divorcing his wife to marry her would not be enough. As the daughter of Emperor Claudius, Octavia was popular with the masses, which made her a threat to both Nero and his new wife. Octavia, therefore, also needed to be discredited and eliminated. To achieve this, Nero falsely accused Octavia of committing adultery with the prefect Anicetus, whom he persuaded to “confess” to the affair. She was also accused of aborting a child she had conceived with Anicetus, a practice that was not illegal but was disapproved of. As punishment, Tacitus writes, Nero confined her to the island of Pandataria (modern‐day Ventotene), off the west coast of Italy:

No exile ever filled the eyes of beholders with tears of greater compassion . . . After a few days, she received an order that she was to die . . . She was then tightly bound with cords, and the veins of every limb were opened; but as her blood was congealed by terror and flowed too slowly, she was killed outright by the steam of an intensely hot bath. To this was added the yet more appalling horror of Poppaea beholding the severed head which was conveyed to Rome.

The oil painting “Revenge of Poppea” by the 19th‐ century Italian artist Giovanni Muzzioli depicts the moment that Poppaea gloats over the severed head of Octavia, presented to her on a plat‐er. Nero’s new wife reclines on a couch, leaning against the emperor, who appears markedly indifferent to the gruesome sight of his ex‐wife’s disembodied head. By contrast, two senators to his right are visibly shocked. The clothing, furniture, and art that decorate the walls in this painting were carefully designed by the artist to depict Rome in the A.D. 60s It is now displayed in the Civic Museum of Modena, Italy.

Their games had been banned for 10 years, as punishment for a brawl that had broken out in the crowd at a gladiatorial contest when locals clashed violently with spectators from neighboring Nuceria. To cement the loyalty of the Pompeians, Nero reopened it after just five years.

The violence of Nero’s reign, as depicted by the ancient biographers, intensified in the A.D. 60s. Ongoing conflict between the Senate and the emperor fueled conspiracies, and Nero ramped up surveillance. Ofonius Tigellinus, prefect of the Praetorian Guard in A.D. 62, led an effective team of spies, who rooted out alleged conspirators. Accused of defaming Nero, the most dangerous rivals of the emperor met untimely deaths: Rubellius Plautus, Faustus Cornelius Sulla, Gaius Calpurnius Piso, Seneca, and many of their co-conspirators.

But Nero’s policy of eliminating adversaries does not differ much from the behavior of the rulers who preceded him. Augustus, who was celebrated as a great emperor, was arguably as aggressive as Nero when it came to dealing with political opponents, ordering all the heirs of his rival Mark Antony killed, for example.

(If not for Nero, Caligula would be rated the Roman Empire’s worst emperor.)

An older man lays dead in a tub while one man covers his face and 4 others stands by

Learning how to die”It takes a lifetime to learn how to die,” wrote the Stoic philosopher Seneca, whose wisdom led to his appointment as mentor to the young Nero in A.D. 54. At first, Seneca guided Nero toward measured policies but later lost influence over him. In A.D. 65 Nero ordered Seneca to…Read More

Album

Whether an emperor was deemed a champion of the people or a bloodthirsty tyrant depended on the relationship he had with the senatorial class of landowners who wrote the history books. While Augustus safeguarded the privileges of the aristocracy, Nero squeezed them. But the reputations of the two emperors were also shaped by their differing attitudes toward the culture, institutions, and deeply rooted customs of Rome.